TLDR; Collaborating is easier when we know which role we have

Ambiguity, change and uncertainty are inherent to innovation. While these qualities mean that innovation is often exciting, it also means it can be frustrating, especially when you keep hitting wall after wall. I’ve been getting stuck repeatedly in one of my projects recently, and in a conversation about my irritation, I heard a great phrase that really resonated: collaborating becomes easier when we know which roles we play. Once we have defined what everyone brings to the table and who is responsible for what, there’s less of a struggle for territory and more room to build on each other’s strengths. Truly something to think about!

Thinking

Every week, I have at least one great conversation in the News Product Alliance Slack group (sign up if you haven’t already!). And this one was a real doozy, so I wanted to share.

While doing research, I stumbled across this article by Max Speicher, Director of Product Design at BestScret. Titled “Listen to users, but only 85% of the time”, Speicher writes about the pitfalls of data-driven design and how ‘proving everything with numbers’ is stifling to creativity and innovation.

I personally had conflicting feelings about the article. On the one hand, I think that oftentimes, not doing experiments around your designs means that the opinion of the highest paid person in the room ends up being the design you go with, even if that’s suboptimal. Same goes for developing new products: if the executives want it (because they suffer from shiny object syndrome, for instance) and there’s no culture of doing research to test ideas before we build them, you end up with one or more failed products.

On the other, I think Speicher has a point when he says that designs (or products) that are truly novel might not immediately resonate with users. In that case, a quick and dirty experimentation style, as we often see in lean(ish) organizations, will not produce positive results. That could mean the idea gets shafted even though it would have had a positive impact on the business if the experiment had been given more time (say, a couple of months) for users to get adjusted.

I shared the article in the NPA Slack to hear what others had to say about it and I ended up in a very thoughtful conversation with Damon Kiesow, Knight Chair in Journalism at Mizzou, and Paul Rissen, Senior Product Manager at Reach PLC. These were my main takeaways:

It’s important to make a distinction between being data-informed and being data-driven. “[Doing experiments (qualitative or quantitative)] doesn’t absolve you of the responsibility for making decisions” (Rissen).

Over-relying on numbers is similar to the ‘appeal to authority’ cognitive bias: just because the data tell you something, “doesn’t mean you don’t have to do the messy critical thinking required when interpreting human needs and behaviors” (Kiesow).

Trying to completely de-risk an idea through experimentation will make it harder to end up with creative, innovative solutions. “[Y]ou need to use data to get 80% of the way to an answer and let creativity and intuition the rest of the way”. (Kiesow)

It’s not hard to see that ideas and prototypes that are truly different will have a slower adoption rate. (There’s this rather famous Dutch clip from the 90s where people on the street are being interviewed about whether they needed or would use a cell phone and all of them said no). But even radical ideas will have some adoption somehwere, so designing for extreme users first could help arrive at those innovative solutions that will later appeal to a wider user base.

Caveat here: in some cases, it’s dangerous to design for edge-case users first. “[A]ny product with the potential to inflict long-term harm on audiences not adequately represented in the first cohort to adopt” (Kiesow), such as Bitcoin, AI, driverless cars, et cetera, should be properly de-risked to ensure that mainstream users will not suffer from detrimental ethical and/or safety risks.

Think about this: what is the culture of experimentation like at your org? Are you more data-driven or opinion-driven in your product and design decisions?

Finally, treat data as a tool to assist in decision making, but do not allow the metrics alone to determine the decision. Don't lose the forest for the trees. Keep an eye on what really counts — building positive long-term relationships that add value to users’ lives, and don't damage them. (Nielsen Norman, 2021)

Learning

We’ve all been in meetings that go off the rails. And if you’re doing innovation work, you might end up in tense situations more often than others. After all, you’re often requiring different teams with divergent interested to work together, and that might lead to some resistance or misunderstandings.

So, what to do? This 2017 article from HBR about ‘saving a meetings that has gotten tense’ has the right idea.

“[T]he principal cause of most conflicts is a struggle for validation. This means that most conflict is not intractable because the root cause is not irreconcilable differences, but a basic unmet need.”

In order to relieve tension and get everyone back into a productive mindset, you need to shift focus to the process rather than the problem. You can do this as follows:

Change the tempo of the conversation. Emotions like anger and defensiveness cause arousal in the body — heart pounding, thoughts racing, that kind of stuff. Happiness and connection, on the other hand, are calm emotions that slow us down. A very effective way to change the pace of the meeting is thus to slow down the pace at which you’re speaking and once you have the attention, to lower your voice as well.

Call out what’s happening. Doing this in a matter-of-fact way without blaming anyone specifically for their role, you accomplish tow things: you give everyone a chance to calm down and you turn the situation into an ‘us against the problem’ scenario. To really invite collaboration back in, you have to ask the group to confirm your description of the current process. This creates a shared sense of ownership to improve the situation.

Propose a structure. This should be a process that slows down the pace in the room and invites everyone to be heard.

Honor the agreement. When people continue to be disruptive, you can point out the inconsistency in their behavior vs the agreement you just made together and ask them whether they still want to continue with the agreement or propose a different structure.

I will say that for me, personally, it’s harder to reflect on the process when I’m not in some kind of facilitator’s role, but these tips are really valuable and I will be trying them out soon.

Doing

I’m sure many of you are familiar with creating “how might we” questions — in short, they’re an effective way to shit the conversation from challenges to opportunities for design and innovation.

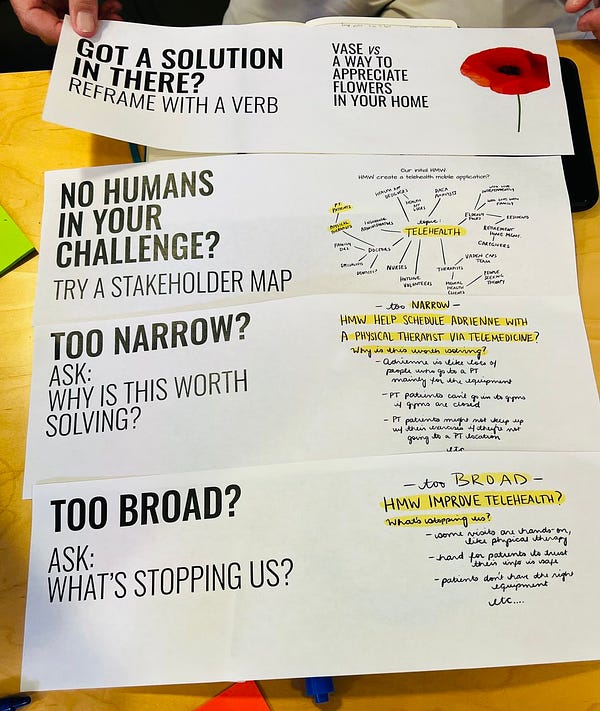

Designing good HMWs is an artform in and of itself. The goal of an HMW is to generate ideas, so if you find that your HMW question doesn’t allow for a variety of solutions, you might need to tweak it a little bit. Recently, I came across a tweet from the Stanford d.school which had a valuable ‘cheat sheet’ for designing great HMWs:

Got a solution in there? Reframe your noun with a verb. HMWs are supposed to generate many different solutions, so don’t limit yourself by baking the solution into the question. “How might we design a better suitcase” is baking in a solution — change the noun with a verb, like “How might we help travelers get their belongings to their destination?”

No humans in your challenge? Try a stakeholder map to find out who you’re design for (and with!). A good HMW is about a real problem for real people. “How might we design a faster app” is a question void of humans and isn’t solving an apparent problem or need for anyone.

Too narrow? Ask: why is this worth solving? If you’re focusing on one stakeholder specifically, you might be little too close for comfort. Zoom out by listing the reasons why this challenge is worth solving, and why-ladder a bit to go even deeper.

Too broad? Ask: what’s stopping us? If your question is “How might we improve journalism?” chances are you’ll feel quite overwhelmed by the task. Break it into pieces by focusing on specific challenges that prevent you from reaching this goal. Chances are, there’s a more concrete problem in there that you can try to solve.

Reading

Let’s look at design from a gender perspective. Gender is an interesting perspective, because it comes with a built-in social hierarchy and distribution of power. In this article, Sanna Rau thoughtfully explains the impact of gender on design and which implications that has.

We need to tell stories, not list bullet points. A guide to making better presentations, starting with what you actually want to say.

Good user interviews aren’t the same as good journalistic interviews. Yes, the skills are transferable, but there are nuances to user interviews that you might not have thought about.

Thanks for reading this week’s issue! If you or your organization needs help with a strategic innovation project, don’t hestitate to reach out. I’m happy to help!